Why the Interstate Massage Compact Misses a Larger Regulatory Opportunity

This article examines the Interstate Massage Compact through the overlooked lens of chair massage regulation, asking whether regulatory priorities have been misplaced.

Over the past several years, a significant amount of attention, funding, and professional energy in the U.S. massage field has been devoted to the proposed Interstate Massage Compact. Its aim is straightforward: allow licensed massage therapists to practice across state lines without navigating multiple, duplicative licensure systems.

Portability matters. For therapists who move frequently, serve mobile populations, or live near state borders, the current system is inefficient and frustrating. The Compact seeks to address a real problem.

But an important question remains largely unexamined:

Is licensure portability the most important regulatory problem facing the massage profession today?

Or has the profession focused on a technically complex issue that affects a relatively small segment of practitioners, while overlooking reforms that could have delivered broader public benefit?

A Solution for a Subset

The Interstate Massage Compact is designed to help massage therapists who wish to practice in multiple states. By definition, this is a subset of the profession. Most massage therapists practice in one state, often in one community, and do not routinely cross state lines for work.

For these practitioners, the primary regulatory challenges are not portability. They are barriers to entry, access to employment, scope-of-practice limitations, and the cost and duration of training relative to earning potential.

From a public-policy standpoint, this distinction matters. Regulation should prioritize changes that produce the greatest benefit for the greatest number—both practitioners and the public they serve. Measured against that standard, the Compact’s impact is limited.

At the same time, one of the most accessible and scalable forms of massage—chair massage—remains constrained by regulations that fail to reflect how it is actually practiced.

Chair Massage: Common in Practice, Absent in Policy

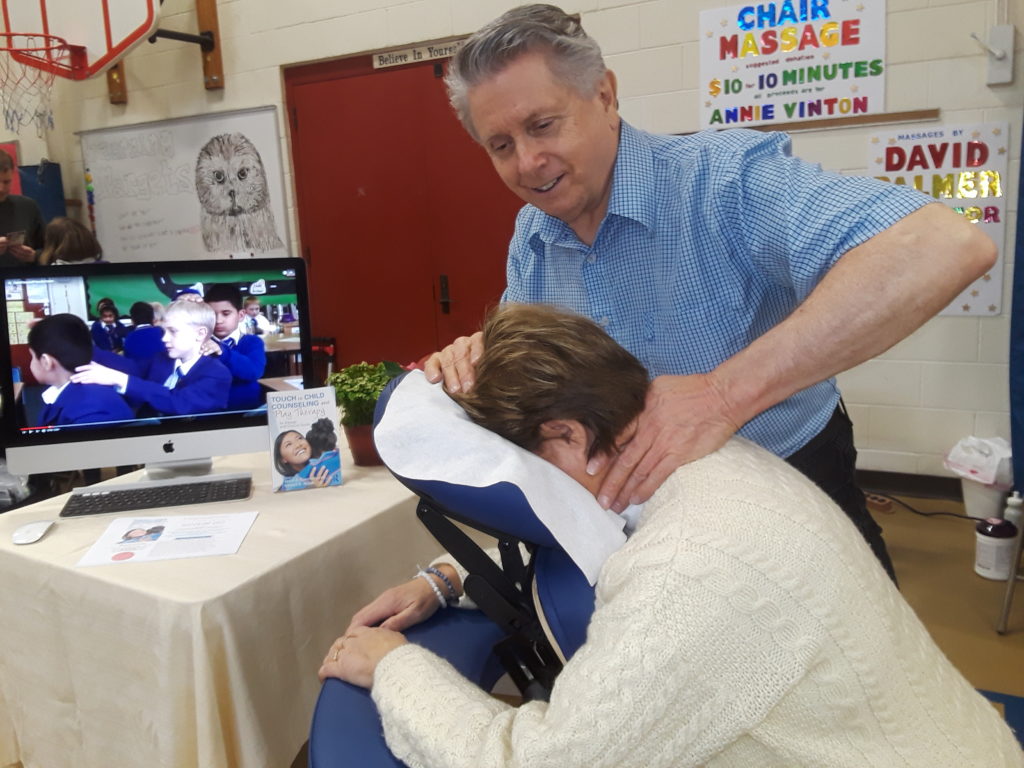

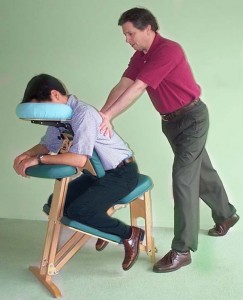

Chair massage is already woven into everyday life. It appears in workplaces, airports, conferences, healthcare facilities, senior centers, and community events. It is typically delivered:

-

Fully clothed

-

In open, observable settings

-

For short, defined periods

-

Without oils, lotions, or disrobing

-

Without diagnostic or therapeutic claims

In terms of risk profile, chair massage is fundamentally different from full-body table massage performed in private rooms. Yet in most states, it is regulated as if that distinction does not exist.

Chair massage is rarely recognized as a distinct modality. Instead, it is folded into full-scope massage licensure frameworks designed decades ago for a different practice context. As a result, practicing chair massage often requires the same regulatory investment—time, money, and education—as practicing unrestricted table massage.

The Consequences of Regulatory Mismatch

When regulation fails to distinguish between different kinds of practice, the result is not increased public safety. It is reduced access.

Overregulation of chair massage contributes to:

-

Fewer practitioners available for workplaces and public settings

-

Higher barriers to entry for new and career-changing practitioners

-

Reduced access to low-cost, preventive, stress-reducing services

-

Missed opportunities in community health and institutional care

Ironically, these outcomes undermine the very goals regulation is meant to serve: public protection, ethical practice, and a sustainable profession.

Good regulation is proportional. It differentiates based on actual risk and context. Treating all massage modalities as if they carry identical risks is not evidence-based policymaking—it is regulatory inertia.

The Opportunity Cost of the Compact

The Interstate Massage Compact has required years of coordinated effort, including federal funding, multistate legislative advocacy, administrative infrastructure, and extensive professional debate.

That investment represents an opportunity cost. Time, money, and political capital devoted to one regulatory pathway are not available for another.

Had even a portion of those resources been directed toward modernizing chair massage regulation, the results could have been immediate and tangible. Potential reforms might have included:

-

Explicit recognition of chair massage as a limited-scope practice

-

Tiered or entry-level credentials aligned with chair massage only

-

Education requirements calibrated to actual risk

-

Clear regulatory guidance for public and institutional settings

Such reforms would not eliminate full licensure pathways. They would complement them—creating legitimate on-ramps into the profession rather than guarding a single gate.

Public Safety and Public Access Are Not Opposites

Advocates of the Compact often frame their arguments around public protection. This concern is valid. But public safety is not enhanced by ignoring meaningful differences in practice context.

Chair massage’s defining characteristics—clothing, visibility, time limits, and public settings—already mitigate many of the risks regulators are rightly concerned about, including boundary violations and misconduct. These features make chair massage particularly well suited to scoped regulation.

Failing to account for these differences does not make regulation stronger. It makes it less precise.

A Question of Priorities

The debate over the Interstate Massage Compact has exposed divisions within the profession about governance, standards, and access. But beneath those disagreements lies a more fundamental question:

What kind of profession is massage becoming, and who is it for?

A regulatory strategy focused primarily on interstate portability benefits established practitioners who already meet full licensure standards. A strategy that also modernizes chair massage regulation would serve a wider range of stakeholders: new entrants, community programs, employers, institutions, and the public.

Conclusion

The Interstate Massage Compact may still move forward, and it may ultimately benefit a segment of the profession. But it is worth acknowledging what was not pursued with the same urgency.

Chair massage—safe, public, and widely accepted—has been hiding in plain sight, constrained by regulations that no longer reflect reality. If the goal of regulation is truly to protect the public while supporting a healthy profession, then the energy spent chasing portability may have been better spent opening doors.

The next chapter of massage regulation should focus less on crossing state lines—and more on removing the barriers that no longer make sense.

But in pursuing this necessary goal, the profession has created an unintended casualty: accessibility. More specifically, we’ve allowed the regulations designed to address the real risks of table massage to inadvertently stifle a fundamentally different practice—chair massage—that poses none of the same concerns while holding the promise of dramatically expanding the market for all massage services.

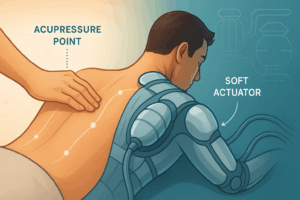

But in pursuing this necessary goal, the profession has created an unintended casualty: accessibility. More specifically, we’ve allowed the regulations designed to address the real risks of table massage to inadvertently stifle a fundamentally different practice—chair massage—that poses none of the same concerns while holding the promise of dramatically expanding the market for all massage services. A new study explores how “smart touch” technologies could expand the reach of manual therapy

A new study explores how “smart touch” technologies could expand the reach of manual therapy

I met

I met

![[Jim Everett and David Palmer tinkering with the massage chair]](http://touchpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/JiM_DP_tinkering.jpg)

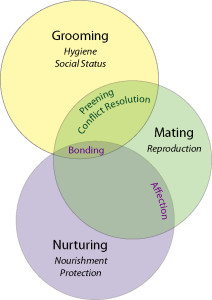

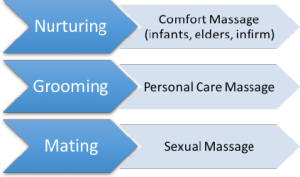

Often overlooked in the ongoing quest for a coherent identity for the massage profession are its evolutionary roots. In other words, what is the genetic basis for what we now call massage?

Often overlooked in the ongoing quest for a coherent identity for the massage profession are its evolutionary roots. In other words, what is the genetic basis for what we now call massage?

All massage done today by trained practitioners can trace its roots to at least one of these instinctual categories touching.

All massage done today by trained practitioners can trace its roots to at least one of these instinctual categories touching. One important characteristic of all touching is the intention of the person initiating the touching. Much of the time the intention behind the touch is not conscious or it is presumed. However, adding conscious intention adds a deeper level of connection to the touch interaction.

One important characteristic of all touching is the intention of the person initiating the touching. Much of the time the intention behind the touch is not conscious or it is presumed. However, adding conscious intention adds a deeper level of connection to the touch interaction. Skin stimulation (touch) is essential to the development and maintenance of health and well being in every human. Why then has it been so neglected as a subject for legitimate inquiry except perhaps by poets? The other four senses have garnered reams of research, had university departments dedicated to them and whole occupations given over to the cause of hearing, seeing, tasting and smelling. But where is the profession dedicated to touching? Touch is truly the “orphan sense.”

Skin stimulation (touch) is essential to the development and maintenance of health and well being in every human. Why then has it been so neglected as a subject for legitimate inquiry except perhaps by poets? The other four senses have garnered reams of research, had university departments dedicated to them and whole occupations given over to the cause of hearing, seeing, tasting and smelling. But where is the profession dedicated to touching? Touch is truly the “orphan sense.” Professional massage practitioners are not the only ones who make money touching. A growing movement gaining traction in our disembodied world brings groups of unrelated people together for non-erotic touch interaction.

Professional massage practitioners are not the only ones who make money touching. A growing movement gaining traction in our disembodied world brings groups of unrelated people together for non-erotic touch interaction. Chair massage often turns out to be just the right introduction people need to experience the joys and benefits of all varieties of structured touch. While not all

Chair massage often turns out to be just the right introduction people need to experience the joys and benefits of all varieties of structured touch. While not all  Over the past three decades American culture has become increasingly touch averse. While few question the importance of touch for the healthy development of newborns, infants and young children, something unfortunate begins to happen about the time kids get ready for school. They learn to fear touch.

Over the past three decades American culture has become increasingly touch averse. While few question the importance of touch for the healthy development of newborns, infants and young children, something unfortunate begins to happen about the time kids get ready for school. They learn to fear touch.

Here is a recent email from a massage student:

Here is a recent email from a massage student: Contrary to what many massage schools would have you believe, chair massage is not simply “table massage lite.” Any successful chair massage entrepreneur will tell you that it is a specialty. So the first step is to become a specialist. You can read books, take classes, and research chair massage on the Internet but there is no substitute for hands-on experience.

Contrary to what many massage schools would have you believe, chair massage is not simply “table massage lite.” Any successful chair massage entrepreneur will tell you that it is a specialty. So the first step is to become a specialist. You can read books, take classes, and research chair massage on the Internet but there is no substitute for hands-on experience. At 31 years, there is little doubt The Walt Disney Company is the oldest continuing corporate supporter of seated massage in the world. Michael Neal began taking a stool around the Disney campus in 1982, providing employee-paid massage. When he retired 18 years later, another practitioner who had also begun working at Disney, Allen Chinn, was ready to pick up the baton from Neal. Besides continuing to work on employees, Chinn occasionally gets paid directly by Disney for individual events such as health fairs.

At 31 years, there is little doubt The Walt Disney Company is the oldest continuing corporate supporter of seated massage in the world. Michael Neal began taking a stool around the Disney campus in 1982, providing employee-paid massage. When he retired 18 years later, another practitioner who had also begun working at Disney, Allen Chinn, was ready to pick up the baton from Neal. Besides continuing to work on employees, Chinn occasionally gets paid directly by Disney for individual events such as health fairs.