For as long as people have been paying for therapeutic massage services, practitioners have feared being mistaken for prostitutes. That fear was the primary driving force that, in 1983, led the American Massage Therapy Association to re-brand “massage” into “massage therapy” in an attempt to define it as the health care profession. [Related article] I call this quest for professional legitimacy the “acceptability” strategy.

For as long as people have been paying for therapeutic massage services, practitioners have feared being mistaken for prostitutes. That fear was the primary driving force that, in 1983, led the American Massage Therapy Association to re-brand “massage” into “massage therapy” in an attempt to define it as the health care profession. [Related article] I call this quest for professional legitimacy the “acceptability” strategy.

Within a decade this strategy was almost universally embraced by massage schools, educators, associations, regulators and vendors serving the industry. It seemed like an obvious strategy and the perfect solution. In point of fact, it was remarkably successful at validating therapeutic massage in the public mindset.

Unlike 20 years ago, nowadays no one blinks twice when a young woman announces her desire to attend massage school–no snickers, no raised eyebrows. The public generally perceives that there is a clear distinction between adult entertainment massage and therapeutic massage. The battle for acceptability has, for the most part, been won.

But now there is another front that needs our attention. What I call the “accessibility” problem.

While we have steadily increased the numbers of people who want a massage, the number of people who actually can get a regular massage has barely budged from less than 5% of the US adult population [see related article]. The reason is painfully simple. Massage therapy is too expensive.

Since I am writing to a primarily professional audience, let me do a quick reality check. How many readers pay full price for at least one massage every two months? How many of your friends do? If you are at all like the typical massage practitioner in my continuing education classes, you can’t afford to pay $65 for a regular table massage, and neither can your friends. The primary reason people don’t get a massage is because they can’t afford it.

The only two significantly expanding models for massage services are the pay-by-the-month model pioneered by Massage Envy and chair massage in malls delivered by Chinese immigrants. What they both have in common is that they are lowering the price of massage.

Those of you who have experimented with online coupons also know what I am talking about. Discount massage shoppers rarely turn into full price regular customers. The only people who pay full price for regular table massage are the very wealthy, the very fanatical, and the very desperate people in pain.

While turning “massage” into “massage therapy” made our services more acceptable, it did little to make them more accessible. In fact, there is a case to be made that the effort to make massage into a health care profession has actually limited its growth.

Massage as health care

When you define massage as massage therapy in a health care context you are defining it as a treatment. The problem is that most massage is not performed as a health care treatment. Most massage, according to consumer surveys, is done for health promotion and relaxation. That has resulted in a huge disconnect between what massage practitioners think they are selling and the general public is looking to buy.

Massage schools graduates are encouraged to believe that they are training to become a health care professional–sort of junior physical therapist. [Indeed, I just searched “Physical Therapy Training” in Google and one of the three sponsored ads at the top was for a massage school.] But the reality is that the vast majority of graduates, if they are lucky enough to be working at all, will be doing massage, not massage therapy. While it may increase school enrollment to have them think otherwise, it does nothing for their level of frustration when the inner image of practitioners does not jive with their outer experience.

For massage customers, particularly new ones, defining massage as therapy often leads them to believe they have to have something wrong in order to get a massage. Every day that I work in a chair massage studio new customers invariably feel obligated to have a physical problem before they step through the front door. “I woke up with a pain in my neck/back/shoulder,” being the most common statement.

Massage as personal care or fitness

If we want to make massage truly accessible, we need to recognize the difference between massage as a health care service and massage as a personal care service.

Defining massage as a health care profession only makes sense for that small, highly trained and experienced segment of practitioners that actually performs massage as treatment and for that small fraction of the public that actually needs and wants to pay for that service. Massage therapy should be defined for what it actually is–medical massage–and we should require far more than the standard 500 hours of training. Something closer to 2,300 or 3,000 hours of the Ontario and British Columbia models would be appropriate.

I admit that I am very conservative on the issue of training but, in my experience, 500 or 600 hours of training to become a massage therapist is totally inadequate, does nothing for creating credibility as a health care profession and sets totally unrealistic expectations for massage school graduates, the vast majority of whom will never make even a part-time living doing massage.

“Massage therapy” should never have been defined as entry-level into the profession. It is not. Plain old circulation/relaxation/prevention-oriented “massage” is entry-level. Let students focus on learning how to touch and be touched [Related article].

Massage has always rested comfortably in the personal care services arena along with spas, hair salons and nail studios. Over the past twenty-five years, massage has also grown up with the wellness and fitness industries. These two economic sandboxes are where the majority of massage practitioners should be playing and it is the kind of massage that massage schools should be selling and teaching.

Radically reinventing an industry

Knowing what we now know, if I was creating the U.S. massage industry from scratch, here is how it would be structured:

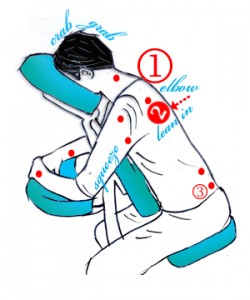

- Entry-level into the field should be a 200-hour course in chair massage.

- Table massage would be a second, optional level of training. Add on another 300-hours to make the current 500-hour standard and have the focus be on training practitioners to be wellness educators as well as table practitioners.

- Massage Therapy would be true medical massage and require at least a masters level program.

There are some strong arguments for making chair massage entry-level. For the industry, chair massage provides a strong foundation:

- Chair massage is what the general public can afford and, because there is no disrobing or private rooms required, is more likely to try.

- Because it is affordable, people will get massaged more regularly.

- People who have had a chair massage are more likely to consider having a table massage or massage therapy.

- The net result will be far more work, more jobs, more successful students, and more sales for chair and table manufacturers.

For the budding massage practitioner, starting with chair massage will eliminate a lot of needless heartache and financial burden:

- Since there is really no way of knowing whether you will like doing massage professionally until you get into massage school, a 200-hour tuition mistake is a lot less painful than a 500-hour mistake.

- More students will be able to afford to go to massage school without going deep into debt and actually make a living doing upon graduation.

- After they are making a living doing chair massage, chair practitioners can save up money to pay for table massage school without taking out loans.

- It is easier for entrepreneurs to open chair massage businesses than table massage establishments resulting in more jobs.

The bottom line

Can my ideal industry model become real? Realistically, I doubt it. The massage schools, associations and regulatory agencies are far too entrenched to consider reforming the profession so radically. The quest for acceptability as a health care profession continues to be seen as the primary goal. Too bad. A lot of people just need to feel better through touch.

Note: This is the third in a series of four articles called “C”-ing Your Way to Success about the value of

Note: This is the third in a series of four articles called “C”-ing Your Way to Success about the value of

This is one of the most common questions I hear from customers. It’s an important question and the response needs to be considered carefully because the answer will set the character and tone of all future interactions with that customer. I am going to offer a response that I have found creates the healthiest relationships with my customers.

This is one of the most common questions I hear from customers. It’s an important question and the response needs to be considered carefully because the answer will set the character and tone of all future interactions with that customer. I am going to offer a response that I have found creates the healthiest relationships with my customers. Laura Allen

Laura Allen  The year was 1983 and the oldest national association of massage practitioners was about to change the face of an industry by turning “massage” into “massage therapy.” This is the story of what led up to that moment.

The year was 1983 and the oldest national association of massage practitioners was about to change the face of an industry by turning “massage” into “massage therapy.” This is the story of what led up to that moment. While having conviction about your work is fundamental to a successful value-based business, a second tool, clarity, is required to effectively communicate your conviction to the rest of the world so they can beat an enthusiastic path to your doorstep. Clarity has a number of important characteristics as it applies to business.

While having conviction about your work is fundamental to a successful value-based business, a second tool, clarity, is required to effectively communicate your conviction to the rest of the world so they can beat an enthusiastic path to your doorstep. Clarity has a number of important characteristics as it applies to business. Admittedly, since my oldest grandchild just entered second grade this year, I have been out of the loop regarding school board policies dealing with public displays of affection (PDA) between students. I guess, after watching Glee for three years, I had thought schools were getting more enlightened about the subject of consensual, non-sexual touch.

Admittedly, since my oldest grandchild just entered second grade this year, I have been out of the loop regarding school board policies dealing with public displays of affection (PDA) between students. I guess, after watching Glee for three years, I had thought schools were getting more enlightened about the subject of consensual, non-sexual touch. Which profession should hold the keys to the storehouse that contains all of the world’s knowledge about human touch? Besides bodyworkers, is there any other (legal) occupation with more practical and theoretical knowledge about touch? I don’t think so and yet I have been struck by the fact that the massage profession often seems to relate to touch the same way fish relate to water. We take it for granted.

Which profession should hold the keys to the storehouse that contains all of the world’s knowledge about human touch? Besides bodyworkers, is there any other (legal) occupation with more practical and theoretical knowledge about touch? I don’t think so and yet I have been struck by the fact that the massage profession often seems to relate to touch the same way fish relate to water. We take it for granted. For an entrepreneur, conviction is where it all starts. An exciting idea enters your brain and gets your juices flowing. You can’t stop thinking about it so you start testing the idea out in conversations with friends. After that reality check you begin making lists of considerations and steps to take to test out until you finally become convinced that you have to make the idea real.

For an entrepreneur, conviction is where it all starts. An exciting idea enters your brain and gets your juices flowing. You can’t stop thinking about it so you start testing the idea out in conversations with friends. After that reality check you begin making lists of considerations and steps to take to test out until you finally become convinced that you have to make the idea real. The first time we nervously walked into Apple Computer’s Macintosh division in 1984 to provide seated massage with our matching grey slacks, white polo shirts and blue blazers, we felt overdressed. At a time when the largest computer company in the world, IBM, was still requiring dark suits, white shirts and ties on all of its workers, while Apple employees were all about jeans and T-shirts. We immediately breathed a sigh of relief and settled in for a year that would change the massage industry forever.

The first time we nervously walked into Apple Computer’s Macintosh division in 1984 to provide seated massage with our matching grey slacks, white polo shirts and blue blazers, we felt overdressed. At a time when the largest computer company in the world, IBM, was still requiring dark suits, white shirts and ties on all of its workers, while Apple employees were all about jeans and T-shirts. We immediately breathed a sigh of relief and settled in for a year that would change the massage industry forever. Last week Phuket, Thailand, featured two of its most famous tourist attractions–beaches and massage–as the Ministry of Health hosted one of five preliminary events leading up to an official attempt in November to break the Guinness World Record for most simultaneous massages (currently at 232 held by Tourism Victoria Australia).

Last week Phuket, Thailand, featured two of its most famous tourist attractions–beaches and massage–as the Ministry of Health hosted one of five preliminary events leading up to an official attempt in November to break the Guinness World Record for most simultaneous massages (currently at 232 held by Tourism Victoria Australia). When I first began developing chair massage sequences in 1982, one of my students was also a student of

When I first began developing chair massage sequences in 1982, one of my students was also a student of  The author of The Medium is the Massage,

The author of The Medium is the Massage,  We all believe in the importance of fitness. Heck some of us are selling it. But what is fitness, and how do you achieve it?

We all believe in the importance of fitness. Heck some of us are selling it. But what is fitness, and how do you achieve it? After an operation in 1974 put my right shoulder out of commission for a couple of months, I realized how little dexterity I had in my left hand relative to my right. What’s that all about, I thought. Who made that dominant hand rule that we live our lives by anyway? What’s so great about only developing half my body.

After an operation in 1974 put my right shoulder out of commission for a couple of months, I realized how little dexterity I had in my left hand relative to my right. What’s that all about, I thought. Who made that dominant hand rule that we live our lives by anyway? What’s so great about only developing half my body.